This post originally appeared on JSI.

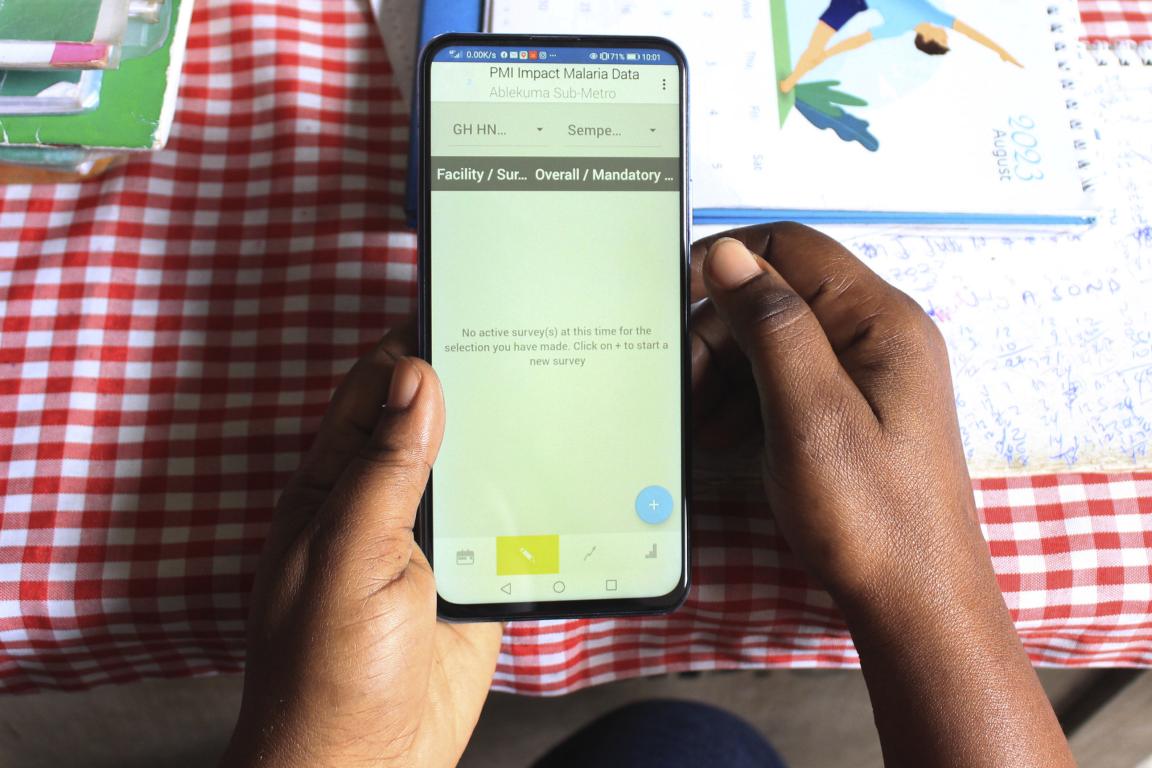

In a busy peri-urban health center in the Jamestown district of Accra, Ghana, Eunice opens her mobile phone and clicks on the supervision app. She is part of a team that is conducting digital integrated supportive supervision activities to improve clinical service delivery.

“I’ve been using the digital supervision app now for about two years,” Eunice says. “As you can see, there are hundreds of facility records stored on here that we have supervised, and you can see more easily where the clinics have improved over time, and what their needs are. Supervision is an important part of my work as it supports health staff to improve their skills and services to their communities.”

The World Health Organization defines supportive supervision as the process of helping health care workers improve their performance in a respectful, non-authoritarian way, with a focus on using supervisory visits to improve knowledge and skills. Traditionally conducted using bulky, paper-based tools, this approach posed multiple challenges for supervisors like Eunice.

“You can often lose your documents from the previous supervision visits, as much time might have lapsed between visits,” she says. “The papers aren’t organized well and therefore it would take me a lot of time to prepare for the supervision visit by having to sort through the paperwork, locate files and the relevant data I need. It was cumbersome and drained me of precious time that I would rather dedicate to coaching and mentoring facilities that need support.”

There are no global standards for supportive supervision systems across health areas, which leads to variable implementation of parallel systems. Ghana is one of the countries that is working to mitigate this fragmentation. Since 2021, the Ghana Health Service (GHS) has led the shift from using analogue supportive supervision records to a streamlined, digital app built on the Health Network Quality Improvement System (HNQIS) on tablets and smartphones, which has integrated all health technical areas. A team of selected supervisors across Ghana now use HNQIS. For example, Eunice, a trained nurse midwife, conducts quarterly supervision on maternal, newborn, and reproductive performance indicators under the leadership of the regional integrated supportive supervision (ISS) team.

On the day of Eunice’s supervision visits, she selects the facility from a drop-down list and observes clinical staff there. She also administers a checklist of key indicators.

“This is done to identify competency gaps for coaching, service improvement, and follow-up,” Eunice says. “After me and the team have finished with our activity, we meet with the facility management and brief them on our key findings. Digital action plans are then developed with the facility staff and the supervisor on the areas that need improvement before a follow-up visit is digitally scheduled.”

Ghana’s investment in digitizing ISS is not an isolated example, as digital tools for frontline health workers have proliferated and systems to share data with supervisors and district managers have been developed. The USAID-funded Country Health Information Systems and Data Use (CHISU) program, led by JSI and partners, recently developed Digital Approaches to SS: Guidance Framework to standardize the approach and language for digital health actors to discuss digital interventions that can strengthen supportive supervision systems and make them more data-driven. The framework is designed to help country decision-makers identify and select digital interventions that are appropriate for their context.

GHS’s leadership and commitment to transforming ISS has made work more efficient for supervisors like Eunice who juggle significant clinical and supervisory duties. Ghana’s ISS model is an example for other countries that want to enable regional and district supervision teams digitally, and can improve the way health care is delivered through close mentorship, coaching, action planning, and follow-up.