Malaria is a significant public health problem in Kenya, with nearly 4,000 people (most of them children) dying from the disease every year—and a significant proportion of the population is at risk of getting it. But between 2015 and 2020, malaria prevalence in the country dropped from eight to six percent. This lower transmission rate means that malaria can be harder to detect in the country—and detection is crucial for early prevention and control measures in order to avoid malaria-related sickness and deaths.

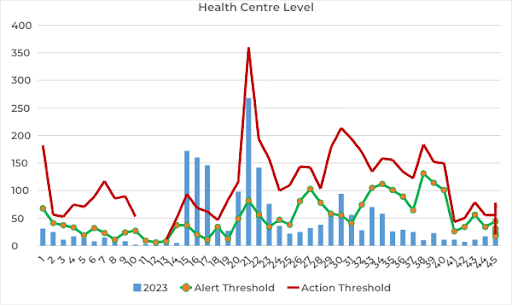

Because malaria transmission has been declining, Kenya’s malaria surveillance guidelines (developed in 2023) recommended revising the way the epidemic thresholds are calculated. CHISU worked with the National Malaria Control Program (NMCP) and the University of Nairobi Health-IT (funded by USAID) to revise the thresholds used in the District Health Information System 2 (DHIS2) epidemic preparedness and response (EPR) application, which automates weekly facility-level malaria data reporting.

CHISU’s support ensured that the revised threshold formula in the EPR application aligns with the malaria surveillance guidelines and enables better epidemic control given Kenya’s low malaria transmission.

“In the case of reduced malaria incidence, the parameters in the revised formula work better with a small case count—giving more accurate thresholds for early detection,” said Hellen Gatakaa, CHISU Kenya Resident Advisor.

NMCP disseminated the updated EPR monitoring application (with financial and technical support from CHISU) during two-day data review fora in November 2023 targeting four counties with relatively high malaria epidemic potential (Baringo, Marsabit, Turkana, and Samburu). Baringo, Marsabit, and Turkana counties have reported frequent malaria outbreaks since 2017, while Samburu County has consistently experienced poor data quality.

Health directors and officers involved in malaria programming (including malaria control coordinators, disease surveillance coordinators, and health records and information officers) from the county and subcounty levels attended these data review fora. The updated application has supported counties’ early epidemic detection so that they can address it quickly.

“The revamped epidemic preparedness and response dashboard boasts an exceptionally intuitive and user-friendly interface, ensuring that the counties have no excuse for being unaware of potential malaria outbreaks,” said Dr. George Wadegu, CHISU County Coordinator. “Equipped with essential tools, the dashboard empowers users to easily and effectively determine or observe the presence of a malaria outbreak in their respective regions.”

Continued monitoring of the revised thresholds will be important—especially because prevalence mapping indicates that more areas of the country are likely to become epidemic-prone in the future. This is in part because of changes in weather patterns (including heavier rainfall) and varying temperatures that allow more mosquitoes to breed.

Major challenges in implementing the updated EPR app include a lack of information technology infrastructure (such as laptops) and insufficient access to Kenya’s health information system at all levels of the health system. Because of these issues, health workers’ and health managers’ use of the app has been lower than anticipated. To help address this, text notifications will be used to send alerts about surges in malaria cases to designated surveillance officers so that they’ll use the app and take action—which could include investigating a possible epidemic and implementing control measures (like case management).

Going forward, further app enhancement may include monitoring deaths and admissions alongside malaria cases—as well as incorporating community malaria data through data exchange with the electronic community health information system.